Bias in the Medical Field

Before even entering their profession, medical students are taught that white (usually male) bodies are the medical standard. Because of this, these students learn how to diagnose and treat white patients, but not patients who deviate from the “medical standard.”

One famous example of this in practice is erythema migrans, a rash which occurs in early-stage Lyme disease. An overwhelming majority of textbooks, medical lectures, and even images on Google only depict this rash on white skin. Because of this, many darker-skinned patients – particularly Black patients – are misdiagnosed or ignored, only receiving the correct diagnosis at a far later stage of Lyme disease compared to white patients. Similarly, because bruises, scratches, and other signs of domestic violence aren't as apparent on darker skin, people often don't recognize the abuse these survivors experience. This can make it even more difficult for survivors to reach out and get help.

In addition to this racial bias, the harmful incorrect stereotype that there’s a biological difference between Black people and white people still pervades medical education. This stereotype correlates with the argument made by some that Black people are “superhuman” and therefore don’t require as much pain medication because of their high tolerance for pain – a myth that has roots in slavery. Some textbooks have even encouraged medical professionals to disregard their patient’s pain response, belittling BIPOC patients and racially stereotyping them. In the eyes of some medical professionals, race makes a person more susceptible to certain diseases; not their environment or surrounding stressors.

Our environment impacts our health, but we know not every environment is equal. Health care workers are, likewise, products of their social environments, and without proper and accurate representation in their training, these medical professionals are forced to knowingly or unknowingly perpetuate this cycle of institutional racism. As a result, the quality of medical care BIPOC patients receive is often grossly lacking.

Racial Inequity in Health care

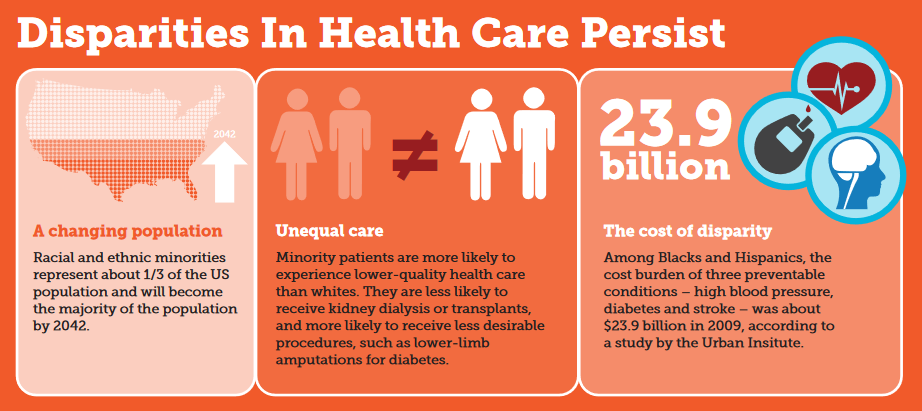

The overall health of most BIPOC Americans is often worse than their white counterparts, though this isn’t always because of poor medical care. While a misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis can severely impact a person’s survival or recovery rate, sometimes patients don’t even have access to basic health care.

People working in low-wage jobs are rarely offered healthcare benefits. When juggling other priorities like rent, childcare, gas, or groceries, paying for private insurance is often an unrealistic luxury – especially when there is still such a large pay gap in our country. Apart from the financial cost, the complexity and stress of applying for healthcare itself can be a barrier, and the process can be particularly difficult for immigrants and non-native English speakers. Although the 2010 Affordable Care Act was created to help increase access to health care and mitigate healthcare disparities, racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage still persist.

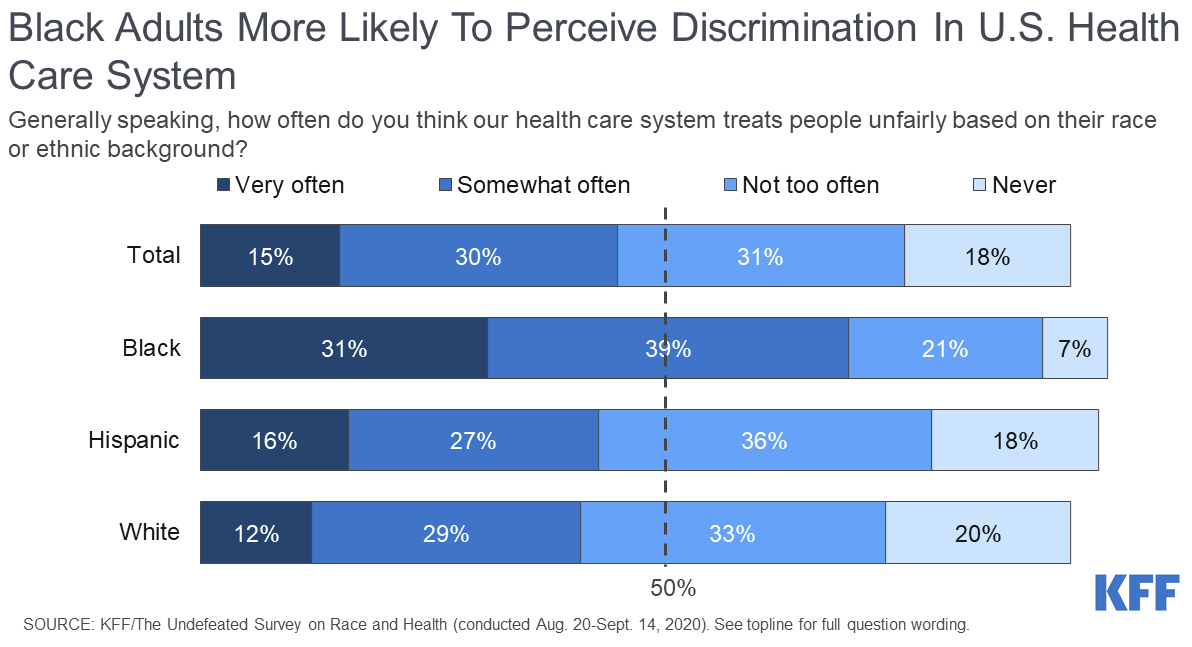

Nationwide, approximately 8% of Americans 18 years or older lack health insurance, but this number isn’t consistent across all demographics. Based on reports from the 2022 US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, approximately 9% of all Black Americans and 17% of all Hispanic/Latinx Americans are living without health insurance. This, coupled with environmental factors, less access to medical care, and a higher likelihood of working in essential “front-line worker” jobs meant Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native American people had the highest number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic’s peak. Rather than seeing this as an indicator that additional resources were needed however, some in leadership framed this tragedy as BIPOC citizens not taking the pandemic seriously enough.

With a long history of victim blaming in medicine, unregulated prescription drug costs, expensive hospital visits, and unequal treatment from healthcare providers, seeking medical treatment can sometimes seem as daunting – or even riskier – than other health concerns.

The Gender Divide

Although there is a disparity in the quality of medical treatment white and BIPOC patients receive, women of every background face a similar gender bias. When talking to medical professionals about their health, women often encounter medical gaslighting, where their medical concerns are brushed off or dismissed as “hysteria” or “psychosomatic”, regardless of the severity of their symptoms. This gender bias is particularly evident for BIPOC patients, who are often stereotyped as “drug-seeking” and refused necessary medication and painkillers because of it. These medical oversights, and lack of care or consideration for patients, result in countless medical emergencies and deaths every year.

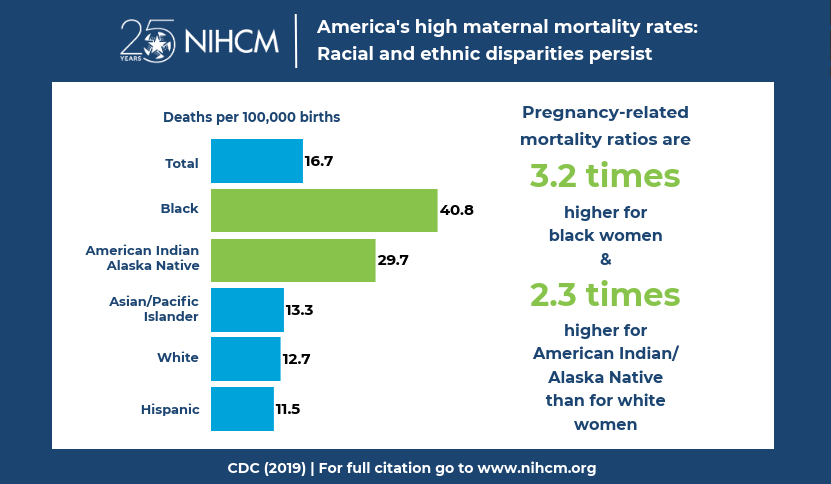

Businesswoman and professional tennis player Serena Williams had her own health scare after giving birth, nearly dying when doctors and nurses ignored her concerns about blood clots, despite her symptoms and extensive history with them. Unfortunately, Serena’s experience isn’t an uncommon occurrence – Black women in the US are three to four times more likely to die from childbirth complications than white women.

The medical system itself is not built to treat women. Not only are many health studies overwhelmingly white, they are also overwhelmingly male-dominated. These decisions have devastating ramifications: women are more likely to experience adverse side-effects from drugs, women are diagnosed with heart disease 5 - 7 years later than men, and women hospitalized with a heart attack are more likely to die from it because the symptoms for heart attacks in women aren’t as widely recognized or discussed as the symptoms men experience.

Next Steps

When certain groups of people are omitted from medical studies, research, and education, the system is built to fail them. With these factors in mind, it’s no surprise that only 34% of women say America’s healthcare is above average (as opposed to 44% of men) while 61% of Americans younger than 50 rate America’s healthcare as average or below average. When such a large majority of the country has doubts in, or objectively mistrusts, our healthcare, it’s clear that the system itself needs reform. To do that, we must recognize and combat the institutionalized racism present within it.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to learn how you can take action to fight inequity today, and save the date for our Annual Stand Against Racism event on May 5.

Ana Rodriguez-Knutsen is the Content Specialist for YWCA's Marketing & Editorial team. From fiction writing to advocacy, Ana works with an intersectional mindset to uplift and amplify the voices of underrepresented communities.

We share the stories of our program participants, programs, and staff, as well as news about the agency and what’s happening in our King and Snohomish community.