How Silencing Women of Color Began

The silencing of indigenous women in the Americas by a white dominating society began as early as Christopher Columbus’ time, when sexual violence, torture, and murder was used by Columbus. This became the standard operating style for the many conquistadors who followed. That terror was often literal; accounts exist of indigenous women’s tongues being cut out to end their protest against the Spanish invaders. The genocide of native peoples included the intentional abuse and murder of women and girls. Those concepts of women of color being sexualized, valueless objects became embedded in conquistador and later American societies.

Forcing black women to use their voices only in service to white people was a key tenet of enslavement. Sexual, as well as physical violence, underscored the danger of speaking out against or trying to escape enslavement. Post-slavery, knowing one’s place was essential for escaping the harshest violence of Jim Crow laws and a lynching culture.

Seattle's Early History of Silencing Women of Color

Our sisters of Asian heritage didn't escape being silenced or sexually exploited. Seattle’s early tradition of numerous brothels, which was carried well into the twentieth century, included those composed completely of women from China, the Philippines, Japan, and other Asian countries. Part of the United States' denial of our history of treatment of women of color is the sexualized abuse reserved for those women with the least power.

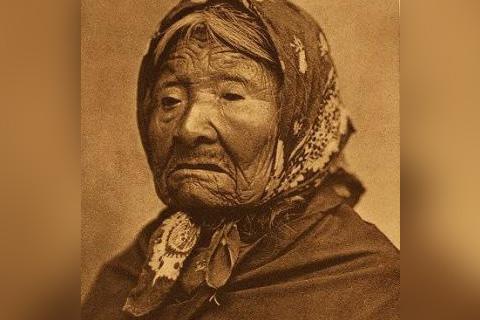

The complicity of the early white citizens of Seattle, in the silencing of women of color extended to Native American women, including those of the Suquamish and Dkhw'Duw'Absh (Duwamish) nations. An example was that of Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Si'ahl (Seattle). Not only was her birth name taken from her and replaced with an entirely different name, one that was easier for white settlers to pronounce, she was largely disregarded and treated as an object of mockery or pity because she was Native American. Although the city of Seattle was named after her father, her entire nation was displaced under the Treaty of Point Elliot.

Men’s voices have precedent; these are the voices we have been conditioned and socialized to hear as informed, wise, objective, and authoritative. American society implies that women’s voices are, uncertain, emotional, shrill, unpleasant, or redundant. Women of color get different messages about the worth of their voices and the consequences of speaking out. Because of this, the lack of women - particularly women of color - in any given dialogue is not usually perceived as a loss. This is not an accident; the historical framework discussed above has given us today's inability to hear women of color's voices.

Stay tuned for Part-two of this series which will be released toward the end of August.

A former prosecutor and trial lawyer, her work has long explored racial equity and social justice issues, including the prevention of violence against women and children, the pervasive nature of state-sanctioned violence against people of color, societal and cultural roles for women, and leadership development for girls and women.

We share the stories of our program participants, programs, and staff, as well as news about the agency and what’s happening in our King and Snohomish community.